Intertextuality & the Prayer of Humble Access

Daniel 9, the End of the Exile, and the Prayer of Humble Access

If you haven’t read it yet, you should check out David Roseberry's excellent discussion of the Prayer of Humble Access, the most distinctly Anglican part of our liturgy.

You can read his post by clicking “Read More” below.

At this point, I don’t think I could count how many times I’ve prayed this particular prayer, and it’s definitely one of my favorite prayers.

For those who might be unfamiliar, the Prayer of Humble Access is prayed near the end of the Eucharistic Liturgy, and it goes like this:

We do not presume to come to this your table, O merciful Lord,

trusting in our own righteousness,

but in your abundant and great mercies.We are not worthy so much as to gather up

the crumbs under your table;

but you are the same Lord

whose character is always to have mercy.Grant us, therefore, gracious Lord,

so to eat the flesh of your dear Son Jesus Christ,

and to drink his blood,

that our sinful bodies may be made clean by his body,

and our souls washed through his most precious blood,

and that we may evermore dwell in him, and he in us. Amen.

The second stanza has an obvious allusion to Matt 15:21–28//Mark 7:24–30. Jesus dismisses the Gentile woman’s plea with the words:

“Let the children be fed first, for it is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs” (Mark 7:27).

She replies:

“Yes, Lord; yet even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs” (7:28).

Because of her faith, Jesus heals this woman’s daughter. In the Prayer of Humble Access, we one-up this Gentile woman. She said that even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs. We say, “We’re not even worthy to gather up the crumbs under your table.” This allusion is pretty apparent, and I’ve noticed it for years.

But tonight, I noticed something new! At least new to me.

The first stanza also contains a fairly obvious allusion to Scripture! In fact, it’s so obvious, I’m a little embarrassed I never noticed it before.

We pray:

We do not presume to come to this your table, O merciful Lord,

trusting in our own righteousness,

but in your abundant and great mercies.

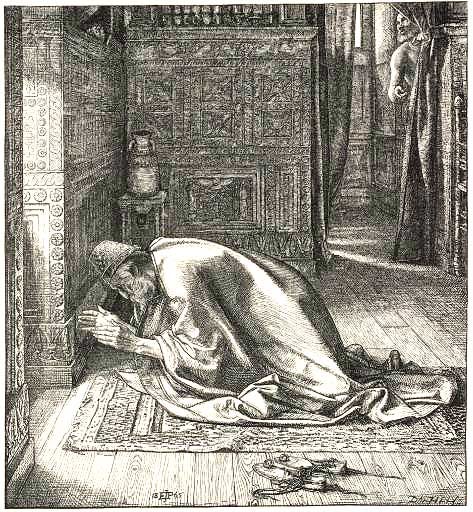

In Daniel 9, the prophet prayed:

For we do not present our pleas before you because of our righteousness, but because of your great mercy (Dan 9:18).

Like I said, that’s pretty obvious. Now, why does this matter?

Daniel 9 is the prophet’s preparatory and penitential prayer in light of (what he thought was) the impending end of the exile.

Daniel 9 begins:

In the first year of Darius the son of Ahasuerus, by descent a Mede, who was made king over the realm of the Chaldeans— in the first year of his reign, I, Daniel, perceived in the books the number of years that, according to the word of the Lord to Jeremiah the prophet, must pass before the end of the desolations of Jerusalem, namely, seventy years (9:1–2).

In case you’re unfamiliar, Daniel is referring to passages like Jer 25:11-12 and 29:10 that claimed the exile would only last for seventy years.

When Daniel finishes praying, the angel Gabriel comes to him and tells him that the exile won’t come to an end in seventy years but in seventy weeks of years. The eschatological timetable of Daniel 9 was “on the ground” in the first century, and it is more than likely what Jesus was referring to when he said:

“The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel.”

If you put together a chronological time table, kingdom-language, and repentance, you’ll find yourself right in the middle of Daniel 2, 7, and 9.

To put it another way (and you’ll need to read my ongoing commentary on the Gospel of Mark for further clarity on this), Jesus and the Evangelists view Jesus’ ministry as bringing about the end of the exile and the accompanying salvation. Jesus launches a new Exodus with a new Passover meal, and in doing so, he brings Israel’s exile to its end. And we, right before we share in that end-of-the-exile meal, pray with the very words that Daniel prayed as he thought the exile was coming to an end.

It’s now thousands of years later, and the point is still the same. We don’t come to God because of anything we’ve done. We come to the table to share in the divine life of Jesus Christ, trusting not in our righteousness but in God’s great and manifold mercy. These words aren’t just distinctly Anglican; they’re inherently biblical.